An earlier post about laminated plane irons asked why manufacturers went to the trouble of making their blades by welding a steel bit on to a wrought iron backing.

As mentioned in the earlier post, there are good reasons for thinking that laminated blades were made to satisfy the demands of end users, but my own conclusions following this bit of research is that the tool makers had compelling economic reasons first and foremost[1].

Raw material costs

Naturally, the price of wrought iron and crucible steel varied over the years, but all the contemporary accounts from the 19th century I have seen agree that there was never a time when the difference was anything other than significant, with the best crucible steel prices reported as being between 5 and 10 times that of wrought iron at various points over this time period.

Considering the lengthy and inconvenient processing required to make crucible steel we can begin to understand why this was so and also to propose some sums to illustrate the economics of making laminated edge tools vs making them from solid steel.

Let's take this comment by Seebohm in 1884 as our starting point:

The accumulated experience of a century has convinced the manufacturers of crucible cast steel that the finest qualities can only be made from bar steel which has been converted from iron made from Dannemora ore. This iron is expensive, its average cost for the last forty years has been at least £25 a ton, the process of converting it into steel is slow and costly the process of melting in small crucibles is extravagant both in labor and fuel and subsequently the best qualities of crucible cast steel can only be sold at a high price.

So called best crucible cast steel is sold at low prices by unscrupulous manufacturers and bought by credulous consumers but though it is quite possible for high priced steel to be bad it is absolutely impossible that low priced steel can be good. The finest quantity of steel cannot be made of cheap material or by a cheap process. Every year the attempt is made and every year it signally fails. No one ever made a better try than Sir Henry Bessemer but his failure was as complete as that of his predecessors. He attempted to produce an article at £6 a ton to compete with one at £60 a ton and failed absolutely.

Henry Seebohm. The Engineer, Volume 58, September 26 1884

In practice Sheffield makers had access to wrought iron produced locally that was much cheaper than the Swedish import, generally selling for less than £10 per ton, but we will use the the less favourable figure of £25 per ton for our sums in case some makers opted to use the more expensive Swedish metal as the backing for their laminated tools.

Assuming that an average bench plane iron weighs around 12oz and the crucible cast steel bit represents about 20% of the weight then you could make ~two and a half thousand laminated blades from:

- 1/5ths of a ton of crucible cast steel

- 4/5ths of a ton of wrought iron

… and the material cost would be £30. If the blades were made of solid crucible cast steel the material costs would be £60.

Labour costs

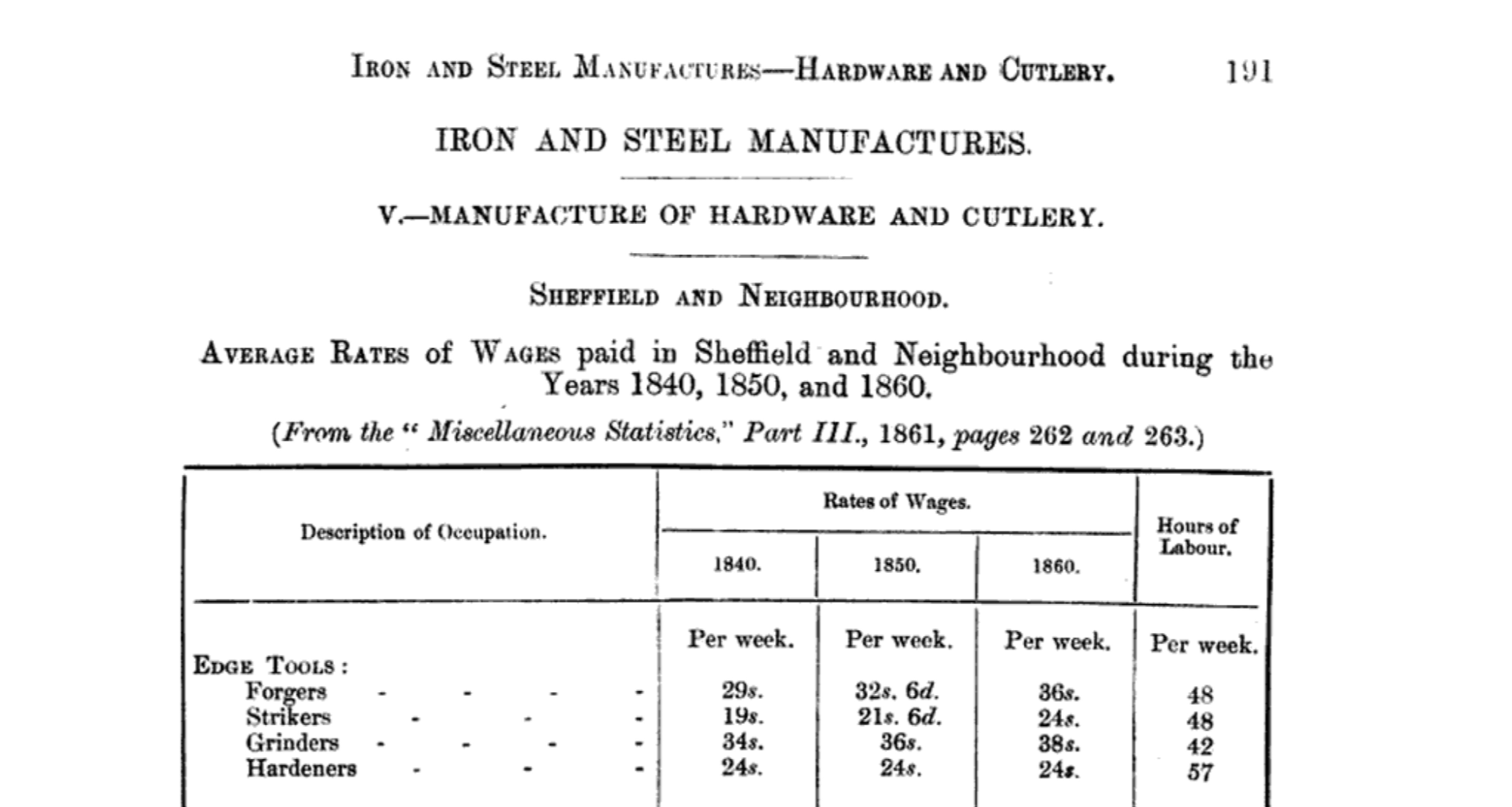

in the 1860s blacksmiths working in Sheffield were paid 36 shillings per week[2]:

Extrapolating from the wage increases for forgers over this 20 year period gives an estimated wage of 48s per week, or about 8s per day, for a blacksmith working in the 1880s. At this time in Sheffield – in fact well into the 20th century – it was common for specialist skills to be hired as ‘little mesters’, meaning the craftsman were self-employed, typically supplying their own tools and renting a small workshop in a works owned and run by a manufacturer.

For the sake of argument, let’s assume that a blacksmith could forge 36 solid plane irons a day. In this case he would need 35 days to forge 2500 chisels, which would then go on to be hardened and then sent to the grinders to be finished[3].

Fuel Costs

We know the tradesman has already to take care of his workshop accommodation and tools from his wages, but let's assume that his employer has to pay for the coal he uses. Again for the sake of argument we will assume he gets through about 80lbs of coal a day[4].

Coal was less than £1 a ton at this time: adding this to the wages gives an actual cost of a days production nearer 9s, thus the total cost of the 2500 solid steel plane irons would be:

| Item | Cost per ton |

| Materials | £60 |

| Wages and fuel for 35 days work | £31 |

| Total | £91 |

Conclusion

We know the tradesman has already to take care of his workshop accommodation and tools from his wages, but let's assume that his employer has to pay for the coal he uses. Again for the sake of argument we will assume he gets through about 80 lbs of coal a day4.

More labour is required of the blacksmith to make a laminated blade and the work should take longer since several heats are needed to complete the tool. Thus although a rival manufacturer competing on price with someone making solid irons would save money on materials (per the above, they need only £30 for each ton of tools, compared for £60 for crucible steel) they would have to absorb the extra work with the remaining £61 left over for wages.

In other words, even if the work rate drop by 50% because of the extra steps laminating the blades the maker would still be able to sell their tools at the same price as the competition.

The economics improve as the output of the blacksmith increase: for instance, if solid steel blades could be forged at a rate of 72 per day, then a tool maker creating laminated blades would only need to produce a 1/3rd of the amount in the same period to for the per-tool cost to equal that of the solid steel blade maker.

And if they could do a gross (12 dozen) per day then the laminated worker would only need to make 1 blade for every 5 the solid-steel worker produced[5].

Perhaps a modern blacksmith could get close enough to the conditions of the time to demonstrate the true time penalty for making a laminated blade compared to making it from solid steel but, absent that, and assuming you accept that it does not take more than double the time to create a laminated blade, it seems reasonable to conclude it was cost effective for 19th tool makers to pay their blacksmiths to do the extra work in order to save on very expensive crucible steel.

One other consideration is mentioned in a paper, On the Manufacturing of Articles of Steel, presented by James Wilson to the Society of Arts in April 1856:

Small articles of cutlery are mostly made entirely of steel, but the shanks and bows of scissors of large size, and the bolsters and tangs of table cutlery, are of iron. This is done for the double purpose of economising steel and facilitating the labours of those who work after the forgers.

The two metals are welded together in a very simple manner. The burning point of steel is much lower than that of iron, and the quality of the steel would be destroyed by heating to incandescence. But iron may be heated to near the melting point without injury. When both are heated to the required degree, they are slightly dipped in a flux, consisting of borax or siliceous sand, and then hammered together.

When the forging is completed, the maker’s name is struck upon the blade, as well as any other distinguishing mark that may be desired. The blades are then hardened by heating to a red heat, and immersing in water.

If the steel be good, it becomes excessively hard and brittle, but its temper and elasticity are given by again submitting it to a moderate degree of heat, which a skilful workman can regulate by watching the changing colour of the steel. This will show the reasons for making the bolsters of table cutlery, &c., of iron. The latter metal is not hardened by the above process, so that the bolsters of table-knives, and bows and shanks of scissors, can be filed and burnished, or “dressed,” by any other process, while the blades are so hard as to resist the operation of a file.

Journal of the Society of Arts v.4 1855-56

the point being that, since edge tools need to be hardened before they can be finished (the heat treatment can cause the steel in the tool to warp), laminated tools are easier, and thus cheaper, to finish since the bulk of the tool remains soft and easy to work.

Stanley and Record

You can read more about the laminated plane irons used by Stanley and Record below

| 1⏎ | at least in the 2nd half of the 19th century, see footnote below for some information about laminated irons made in the 20th |

| 2⏎ | pre decimalisation in the UK (1971), there were 12 pence in a shilling and 20 shillings in a pound |

| 3⏎ | this is a simplification, in practice, as suggested by the rate card above, it was more efficient if the blacksmith work needed to make larger tools was often done by two people working together – forgers and strikers – the strikers using a heavier hammer to draw out the rough shape from the steel bar and the forger refining the shape. c.f this account, referred to elsewhere in this post, which also contains an overview of the other steps needed to make edge tools and cutlery. The paper and subsequent discussion, reported in the same journal, also offer some interesting observations on some of the quality issues that can be caused by incorrect steel choice and poor heat treatment: Journal of the Society of Arts v.4 1855-56. |

| 4⏎ | traditionally coal is supplied in 5 gallon tub containing around 40 lbs |

| 5⏎ | this work rate is perhaps not as implausible as it sounds – at the height of his powers, Albert Craven, one of the last Sheffield blade forgers – could do over two gross of penknife blades in a day. He retired in 1978 – see a fascinating interview with him here |